Solar System Simulation

Planetary simulator

The “Planet X” video spawned from a series of projects of mine that I started when I was 16 back in 2010. It started out when I saw an amazing video by Scott Manley showcasing a timelapse 2D rendering of asteroids in our solar system as they were getting discovered. I thought that this was so incredible, that I challenged myself to recreate it in 3D. I used data from Edward Bowell’s Asteroid Orbital Elements Database.

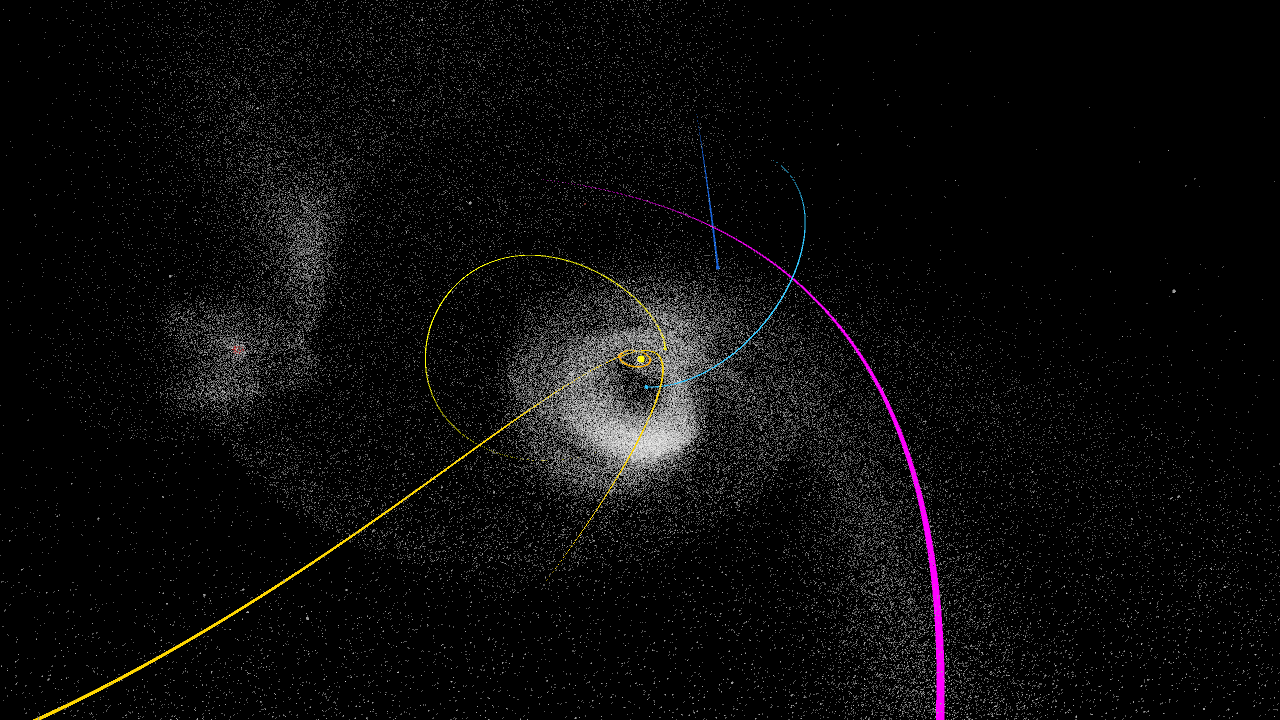

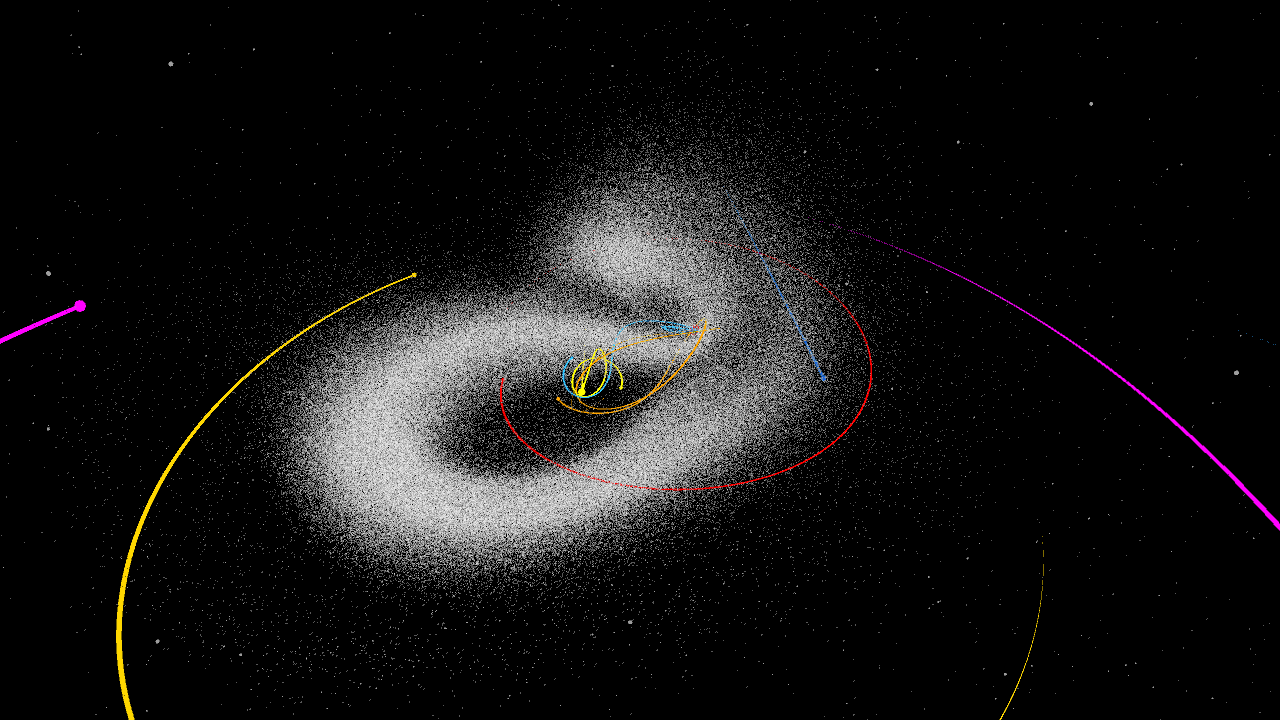

This is what resulted after about a week of trying to decypher all of the Greek symbols and algebra. At the time, the database had about 500,000 asteroids. In this video you can see that the entire asteroid belt completely dips below the solar system plane on one side. A few years later I returned to the project and reworked a lot of the trigonometry. A mismatched sin/cos caused the error from last video. After making some fixes, refactoring the code, and double checking the accuracy of the math, I made a new rendering to the tune of Vivaldi. This time there were 100,000 new asteroids since the last rendering.

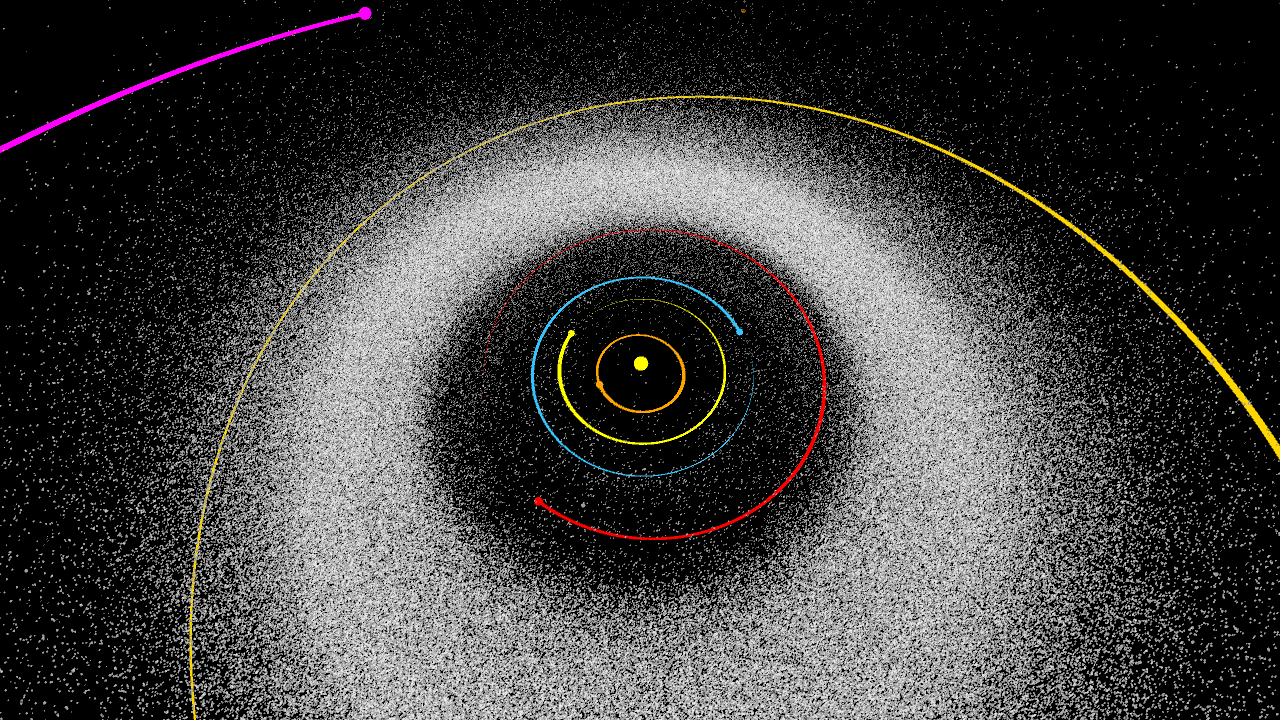

My first two renderings worked by calculating where along each orbit asteroids were using their “orbital elements.” These elements were basically all of the angles and parameters necessary to plot an approximate curve of the path of any given asteroid or planet. It was a grievance to me that this was a plotter and not a simulator, so I started another project with the goal of finding the positions of all these asteroids through physics rather than trigonometric approximation.

First I took all of the equations from the plotter and derived them in order to approximate the velocity of every asteroid in addition to their positions for any given moment. These initial position/velocities worked as the seed to my simulations.

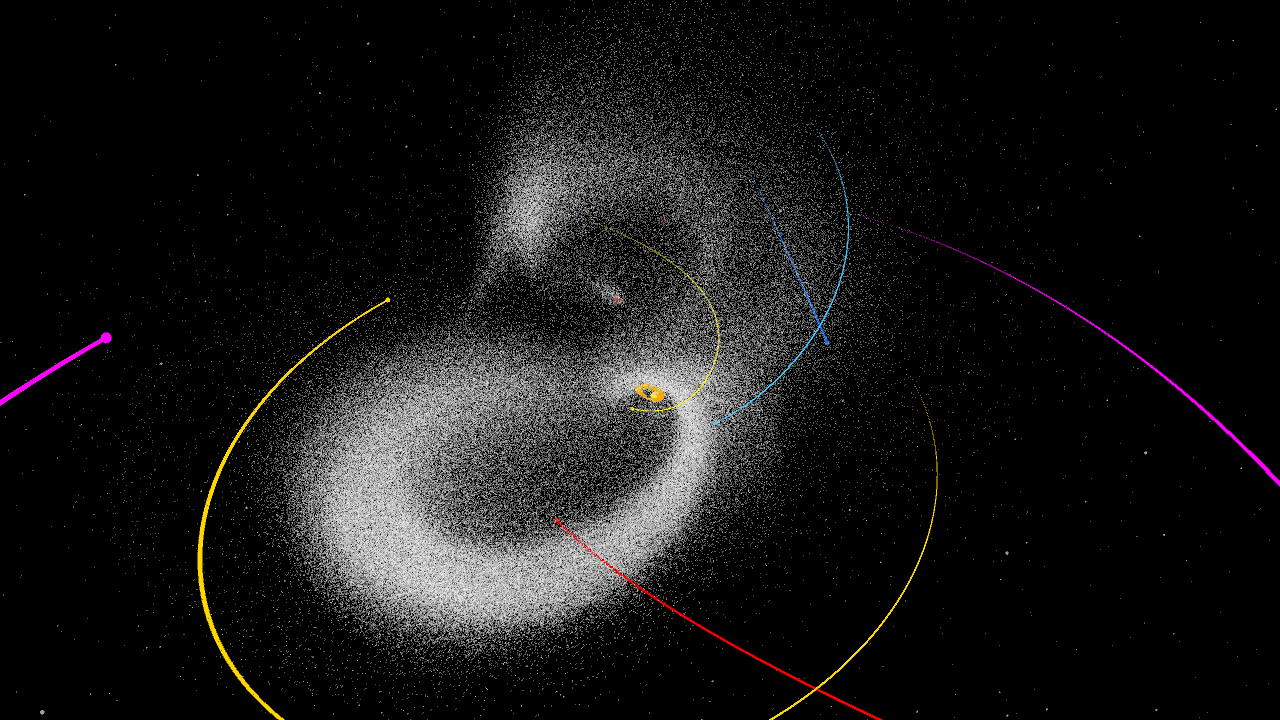

I made two different simulators. The first one used fourth-order Runge-Kutta as an integration method. The second one, after suggestions from astronomers on a forum, used Störmer–Verlet integration. My implementation may have been wrong, but it took up to 100 iterations of Störmer–Verlet to get the same stability as 1 iteration of Runge-Kutta!

Once I had a robust n-body physics engine, I had the freedom to run whatever celestial-scale experiment I wanted. Naturally, my first experiment involved taking this imaginary sun-massed “Planet X,” and setting it on a path through the asteroid belt.